I, like nearly all editors, require my clients to sign a contract prior to beginning work on a new project. Contracts vary greatly from editor to editor, and a single editor might even use different contracts for different types of work. There is one thing that all contracts have in common, however: deadlines.

I, like nearly all editors, require my clients to sign a contract prior to beginning work on a new project. Contracts vary greatly from editor to editor, and a single editor might even use different contracts for different types of work. There is one thing that all contracts have in common, however: deadlines.

An editing contract typically includes two deadlines. The first is the date by which the client must submit all requested materials to the editor, and the second is the date by which the editor must return the edited material to the client. (There may also be other deadlines in the contract, such as deadlines for deposits or payments.) Contracts also typically include consequences to explain what will happen if clients fail to meet their deadlines. For instance, “If the editor does not receive the requested materials by [insert date], the editor cannot guarantee that the work will be completed by [insert date]. The work will be rescheduled at the editor’s discretion and the client will be billed a late fee of $X. If the client terminates the project after failing to meet the [insert date] deadline, the editor will retain the $X deposit/will charge $X/some other monetary penalty….”

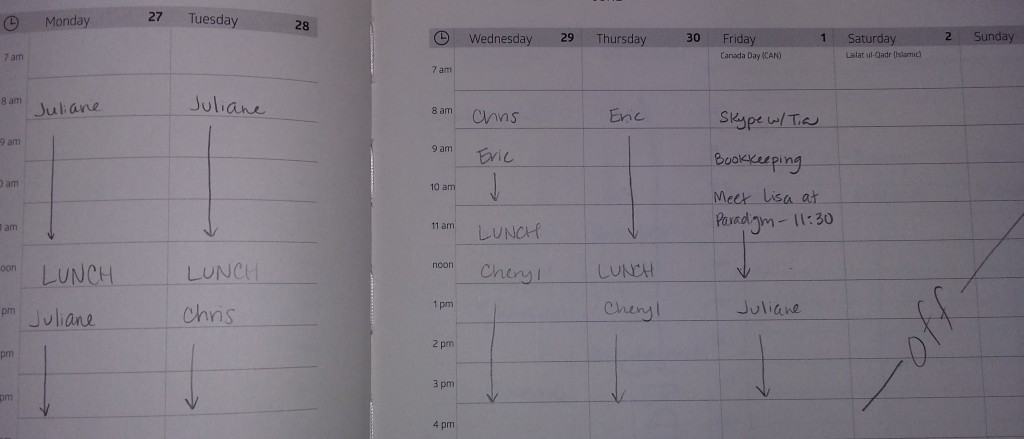

This might seem harsh, but it isn’t when you look at it from the editor’s perspective. I budget a specific amount of time for each project, and I plan in advance when I will work on each one–I have to in order to ensure that I can balance all of my clients, give each project the attention it deserves, and meet the deadlines I’ve set. As long as my clients submit their materials on or before the agreed upon date (which the vast majority do), it all works works wonderfully. I can complete my work as planned and give each project my full focus. Here’s a page from my planner to show what a typical weekly schedule looks like:

On the week pictured above, I worked on projects for four different clients. I also had a Skype conference with a fifth client, and an in-person meeting with a sixth. (And, like most professionals, I took the weekend off.) If my Monday-and-half-of-Tuesday client, Juliane, had submitted her work late, it could have thrown off my whole week. Sure, I could have started on another project if Chris, Cheryl, or Eric had submitted their materials early, but if not, I’d have been twiddling my thumbs for a few days with nothing to do. Then, when Juliane did finally submit her work–whenever that might have been–one of two possible things could have happened. Either I’d have worked nights and weekends to meet the deadline by which I was supposed to return the edited work, or I would have said, “You didn’t meet your deadline and I’ve got other clients, projects, and deadlines to focus on right now. I’ve got a few days free later this month. I’ll pencil you in then. I’ll also have to charge the $X late fee as discussed in our contract to make up for lost pay.” (If this scenario had played out, I would have lost pay; I couldn’t have billed Juliane for work I didn’t complete, and I also wouldn’t have been able to bill another client during the additional time that I reserved for Juliane’s project.)

In the absence of extenuating circumstances, most editors will take the latter option–as they should. It’s not their responsibility to bend over backwards when clients can’t uphold their end of an agreement. Besides, editors have other things to do in the hours that are “blank” on their day planners. They go to writers’ group or serve on a committee in the evenings, sleep in on the weekends, visit Grandma at the nursing home on Saturdays, catch a movie with their spouse on Sunday afternoon. They meet a friend for dinner or a drink, drive their children to piano lessons and baseball practice, and spend half an hour every night winding down with a good book. Editors can’t be expected to drop all of these things because a client inexplicably failed to meet a deadline. Likewise, other clients shouldn’t suffer by having their projects rushed because someone else missed a deadline. (Nor should you and your project suffer because someone missed a deadline!)

For all of these reasons, deadlines are important for both clients and editors. To keep your editor happy–and ultimately, to keep yourself happy–it’s critical to abide by the deadlines that you agree to. If your editor offers you a contract with a deadline that you won’t be able to meet, don’t sign it. Instead, ask the editor to revise the contract to include a deadline that work for you. It’s generally not a problem to do this, and your editor would much rather draft a new contract and schedule you at a more optimal time than have to squeeze you in when you miss a deadline. Your editor would also rather draft a new contract than have an awkward conversation about why you owe some additional money when no additional work was performed.

On that same note, let your editor know right away if unforeseen circumstances arise that will prevent you from meeting a deadline that you agreed to. As noted above re: visiting Grandma in the home and sleeping in on Saturdays, editors are human. We understand that clients sometimes have car accidents, unexpectedly lose friends or loved ones, and have children who get concussions. We’re compassionate and we’ll do what we can to work with you–we try our best to treat clients the way we’d want to be treated. (It’s the right thing to do, but it’s also a good business practice.) If you’re good to us, we’ll be good to you, and if you let us know what’s going on as soon as you can, we’ll do our best to accommodate you.

The key is mutual respect. If you respect the agreement you made with your editor–in other words, if you respect your editor, your editor’s time, and the commitment your editor has made to your project–your editor will also respect you and the agreement that she made with you. My Grandma, the one who I sometimes visit in the home on Saturdays, would say it like this: “One hand washes the other.”