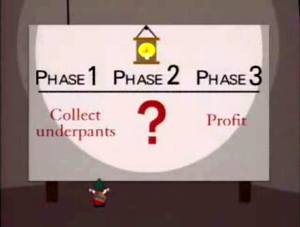

Self-publishing can be a cost-effective way to get your work out into the world. Setting up a title on CreateSpace and then selling it both digitally and in hard copy through Amazon is free. The allure of publishing without jumping through the difficult hoops of query letters and book proposals and agents is certainly enticing. Within just a few days, your book can find its way into readers’ hands, unlike the months or even years you might have to wait with a traditional publisher. The ease and instant gratification can seduce writers into believing that they’ll create a book at no cost and then quickly make money on their novel/memoir/self-help book. It’s sort of like that South Park episode with the underpants gnomes: Phase 1, collect underpants. Phase 2, ???????. Phase 3,Profit.

For authors, Phase 1 is writing the book. Phase 2 should be editing, and then Phase 3 would be to publish and profit (whether through a traditional house  or through self-publishing). If you gloss over Phase 2, like the underpants gnomes, you’re unlikely to reap profits during Phase 3. If your self-published masterpiece is full of grammatical errors, if your characters are flat, if in Chapter 7 you confuse the reader by referencing an event that doesn’t happen until Chapter 9, you’re not going to generate word-of-mouth support (lost sales!), nor will you develop a devoted readership that is excited to buy your next book (more lost sales!). Instead, you’ll get a bunch of negative Amazon reviews so that your book dips lower and lower in the ratings, is less and less likely to be recommended to readers, and sells almost no copies…because who is going to buy a book from an unknown self-published writer that has only a 1- or 2-star rating and a ton of bad reviews? I wouldn’t, and you wouldn’t either.

or through self-publishing). If you gloss over Phase 2, like the underpants gnomes, you’re unlikely to reap profits during Phase 3. If your self-published masterpiece is full of grammatical errors, if your characters are flat, if in Chapter 7 you confuse the reader by referencing an event that doesn’t happen until Chapter 9, you’re not going to generate word-of-mouth support (lost sales!), nor will you develop a devoted readership that is excited to buy your next book (more lost sales!). Instead, you’ll get a bunch of negative Amazon reviews so that your book dips lower and lower in the ratings, is less and less likely to be recommended to readers, and sells almost no copies…because who is going to buy a book from an unknown self-published writer that has only a 1- or 2-star rating and a ton of bad reviews? I wouldn’t, and you wouldn’t either.

A few months ago, I worked with a client who was trying to undo this problem. She’d self-published a memoir on a very interesting topic (hint: it was either sex, drugs, or rock ‘n roll) and her cover art was fantastic. The book appeared, based on its Amazon listing, to be a highly polished and professional production, and the blurb made the story sound fantastic. The title sold fairly well in the weeks following its initial release because of the intriguing combination of subject + cover + blurb. And then, all of a sudden, it tanked.

What happened? The reviews happened. The writer had initially foregone an editor to save money. The resulting book had a confusing plot line and substantial grammatical and mechanical errors. She pissed off people who had paid good money to have a crappy reading experience. They began posting reviews like these: “One of the worse books I have read” and “This book was a lot of incoherent blah, blah, blah. I didn’t care about her, what happened next, or how she was saved” and “Why are there so many comma errors?! It’s distracting. I can’t finish.”

It didn’t matter that the story itself was compelling or the cover art was enticing. Once these reviews appeared, people stopped buying the book. How many dollars did this writer lose in sales? How much could she have made if she’d hired me before she self-published a sub-par memoir? Issuing a revised second edition might help somewhat, if she can elicit enough positive reviews from readers who are willing to overlook her missteps in the first edition, but still. Those initial negative pronouncements will never go away, and the stigma of that first edition is out there. The stain will follow this title and this author forever.

In my last blog post, I wrote about the cost of editing. I addressed the sticker shock that many writers feel when they receive a quote from an editor, discussed the amount of time an editor needs to complete a job, and explained why editors are justified in charging what they do. In short, I explained how much it costs to hire an editor. However, I didn’t address how much it costs not to hire an editor—and, truthfully, this is probably the more important cost for an author to consider.

It’s tempting not to have a dollar amount to record in the “expense” column for your project, which makes it appealing to self-edit. But if you choose that route, what will that decision cost you in two months, or a year, or five years? Many writers fail to take the long view into consideration when deciding whether to hire an editor. They look at the current balance in their checkbooks and don’t think of the potential future balance. This is a rookie mistake, and one that can have huge consequences.

Your readers have standards, and those standards have been shaped by the professionally-produced books they’ve read from publishers like Random House and Graywolf and Penguin—books that received substantial developmental editing, copyediting, and proofing. (This is part of why it takes so long for a book to be released after you sign an agent or a book deal.) Readers don’t lower their standards for self-published books, which means that as a self-published writer, you can’t lower your standards, either. You need to edit your book to make it rise to the level of Random House and Graywolf and Penguin.

You might not have the budget for professional developmental editing, copyediting, and proofing, and that’s OK. Professional editing is best, but there are certainly ways around it. Join a writers’ group and receive developmental feedback that way, or ask a few trusted friends to read your book and offer honest criticism. (Or both! Preferably both!) If you’re a college student, bring a chapter to your campus writing center and ask a tutor to help you identify your consistent technical errors, and then ask the tutor to teach you how to find and correct those errors. If you’re not a college student but live in a college town, call the campus writing center to see if they work with community members. (They probably don’t, but the tutors might want to moonlight, and hiring an English major to help you with your initial edits will be cheaper than hiring an editor.) Even being patient enough to set your manuscript aside for a month before re-reading it can help you to find the errors and inconsistencies you couldn’t initially see.

Still, after taking advantage of these options, it’s wise to hire a professional—me, or someone like me—to give the book a final once-over even if you can’t afford a Cadillac-level edit. The work you put in on your own should significantly reduce the editor’s bill because the manuscript will be much closer to complete, but it’s not a total replacement for professional editing. Novelist Jo-Ann Mapson gave me a valuable piece of advice during my first year of graduate school: “Always send your manuscript out wearing its church clothes.” She’s right. No matter how many times you re-read, something will slip through the cracks. Hiring an editor to catch those stray errors is invaluable because just one snide review about a grammar mistake will cost you sales. A plethora of snide reviews will cost you a lot of sales.

If you’re staring at an editor’s quote and are feeling daunted by the price tag, ask yourself one simple question: can I afford not to hire an editor? As you’re pondering this, think about my client, the one with a book that had a lot of potential, the one who thought her manuscript was clean enough that she didn’t need an editor. Remember her terrible reviews. Remember that in the end, she hired an editor. Remember that, for the exact same price, she could have avoided lost sales and damage to her reputation if she’d only hired an editor up front. Then, take a deep breath, get to work doing everything you can to polish the manuscript on your own, and finally, hire that editor. In a few months, when the positive Amazon reviews begin to stack up and people other than your mom and best friend buy your book, you will be so thankful that you did.