As an editor, there are few things that I hate more than reading fifteen pages of an excellent story or essay, only to have the writer blow it in the last page or two with an unsatisfying (or downright awful) ending.

I wish I could say this was a rare phenomenon, but it isn’t. Every reading period, I encounter a handful of pieces that make me want to reach through the page to shake the writer for daring to conclude something so wonderful with an ending so quick/trite/unbelievable/out of sync. I’ll be reading along, thinking that I’ve found the piece that will be the highlight of the next issue, and then—out of nowhere— it falls apart faster than a genre story gets ripped to shreds in an MFA workshop.

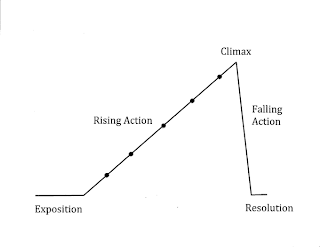

Writers, please stop it. You are selling yourselves short when you don’t give your endings the same attention you give to the rest of your work. You are brilliant! You have skills! Your language is lovely! Your characters are complex and interesting! It’s just your damn endings. Don’t get me wrong—I know that it can be hard to wrap things up, and I sometimes struggle with endings, too. We reach the “climax” on our little inverted checkmarks, and then…what? Our cliché plot diagram reminds us that we’ve still got two steps: falling action (“denouement” if your English teacher is fancy) and resolution. Of course, the possibilities for what you do after the climax are endless, but please, for the love of god, do something.

Writers, please stop it. You are selling yourselves short when you don’t give your endings the same attention you give to the rest of your work. You are brilliant! You have skills! Your language is lovely! Your characters are complex and interesting! It’s just your damn endings. Don’t get me wrong—I know that it can be hard to wrap things up, and I sometimes struggle with endings, too. We reach the “climax” on our little inverted checkmarks, and then…what? Our cliché plot diagram reminds us that we’ve still got two steps: falling action (“denouement” if your English teacher is fancy) and resolution. Of course, the possibilities for what you do after the climax are endless, but please, for the love of god, do something.

An ending doesn’t necessarily need to tie up loose ends—the “too perfect” ending has its problems as well—but it does need to make the work feel complete. Even if the story isn’t fully resolved, the ending still needs to be purposeful. The loose ends should leave the reader contemplating; they should not make the reader scratch her head and think “wtf?”

An ending shouldn’t take a right turn or introduce new information, either. The goal is to make the work feel finished, not blown wide open. Even if there’s going to be a sequel, Part One needs to feel like a stand-alone unit…especially if it’s going to be published in my journal and therefore not marketed as part of a series.

Nor should an ending make the reader feel like she’s suddenly slammed on the brakes after cruising down the Interstate at 70 miles per hour. Furthermore (although this is rare), an ending shouldn’t go on and onand on and on and on and on and on and…

Writer’s Digest recommends an exercise to illustrate just how easy it is to kill a story with a bad ending. Try it: “Take a short piece you’ve written (or whip up a new one) and hack off the ending. Then, write the most awesomely bad ending you can—and see how easily you can derail the piece.” See? Contrary to what is apparently popular belief, endings aren’t throw-away things. They’re critical to the success (or failure) of the work.

I always have this discussion with my freshman comp students after I grade the first paper because it’s so clear to me that most of them hit the page requirement and then just puked some crap onto the page for the final paragraph so that they could run off to play video games or impregnate their girlfriends or whatever it is that they do when they finish their homework. I always tell my freshmen that endings are their last impression—their last chance to convince me to give them an A. When I’m wearing my editor hat, the ending is the writer’s last chance to convince me to publish his/her work…or to not publish it, as the case may be.

I sometimes use the analogy of a job interview. I tell my students that even if they’re appropriately dressed, answer all the questions in a favorable way, and are endearing throughout, they’re not going to get the job if they give the interviewer the finger on the way out the door. Bad endings are kind of like that.

Please, writers, I beg you. When you submit your prose to my literary journal, Stoneboat, don’t make me invest half an hour in your brilliant work only to flip me off on page nineteen. You will not get the job.

This post was originally published on the Stoneboat blog.