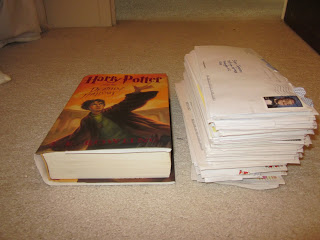

I have been submitting my work to literary journals since 2003 (although only recently have they begun to publish me; the  photo at right depicts my stack of rejection letters next to the seventh Harry Potter book, for scale, and these are only the hard copy rejections — there are plenty more that have come via email*). As someone who has been playing the submission game for quite a while, I’ve created a system. I read the ads in Poets & Writers and The Writer’s Chronicle to find journals that my work seems to fit. I check their guidelines online, then address the cover letter. I print my essay. I use my best handwriting on a large manila envelope and the SASE tucked inside, record the submission on a spreadsheet (a hard copy, even!), mail those over-sized envelopes after standing in a long line at the post office, and then wait anywhere from several weeks to 18 months for a response.

photo at right depicts my stack of rejection letters next to the seventh Harry Potter book, for scale, and these are only the hard copy rejections — there are plenty more that have come via email*). As someone who has been playing the submission game for quite a while, I’ve created a system. I read the ads in Poets & Writers and The Writer’s Chronicle to find journals that my work seems to fit. I check their guidelines online, then address the cover letter. I print my essay. I use my best handwriting on a large manila envelope and the SASE tucked inside, record the submission on a spreadsheet (a hard copy, even!), mail those over-sized envelopes after standing in a long line at the post office, and then wait anywhere from several weeks to 18 months for a response.

Some of my best memories of graduate school are centered around this system — or maybe it’s more accurate to think of it as a ritual. My roommate and I would sit cross-legged on the dingy living room carpet, surrounded by envelopes, highlighters, pens, stamps, and stacks of writing magazines. We always had a laptop on the coffee table, too, so we could Google the journals where we hoped our work might find a home. We’d make suggestions to one another, too: “Your barn story sounds like a good match for Writing Contest X” or “Journal Y is doing a memory theme for the fall issue, so maybe you could send your museum essay.” We did this about once a month; we called it “Send Shit Out Night,” and it was a way to hold ourselves accountable. It made us feel like writers, and it made us feel like we just might be able to shed the “MFA student” label and take on the “published writer” label.

For a long time after moving out of that apartment, I continued to hold “Send Shit Out Night” on my own, just with fewer magazines and not as many envelopes. In recent years, though, the office supplies have worked their way out of my ritual and the laptop has taken on a more central role because most journals have begun to take electronic submissions. This makes sense for a lot of reasons. From the writer’s perspective, the process is far less laborious. It’s also a lot cheaper — no more stamps, envelopes, paper, or printer ink. And from the journal’s perspective, there are fewer SASEs to keep track of, essay pages to keep in order, manuscripts to recycle, and rejection notices to print and sign and mail.

In the last year or so, I’ve noticed that many journals have either eliminated paper submissions entirely or added a note to their guidelines that reads something like this: “Strong preference for electronic submissions.” And that, from the writer perspective, makes me sad. I comply because I don’t want to be on an editor’s bad side just because I sent a hard copy, but I prefer — Ienjoy — the hard copy submission. It feels more substantial to send my words into the world on a sheet of paper; my essays feel more real when they physically exist. Hard copy submissions also make me feel like I’m putting in a more honest attempt at this whole “I’m a writer” endeavor.

Email submissions and submission manager submissions make me feel like I’m half-assing it; anyone can fire off an email or upload a document (theStoneboat email inbox is proof), but it takes real dedication to hand-address a dozen 10×13 envelopes, and a serious attitude to spend $1.50 to mail each one off to a journal (plus the $.44 for the SASE). I kept track of all my submission receipts in 2007. Between envelopes and postage, I spent nearly $100 just to mail my submissions. Let’s break that down: I spent $100 to publish oneessay, for which I was paid with two contributor copies (roughly a $10 value).

But as much as I love hard copy submissions as a writer, I am not so keen on them from the editorial perspective. When Stoneboat receives a hard copy submission, I have to digitize it so that all of our editors have access to it, I have to make sure not to lose the SASE, I usually have to print and sign a rejection letter, I have to write a return address on the envelopes. Individually, none of these tasks take much time, nor do they put a major wrinkle in my day. They are minor — and infrequent — interruptions in the fabric of my editorial work. But when I add up all of those brief interruptions, each hard copy submission takes up a lot more of my time than its electronic counterpart. When I see a 10×13 manila envelope poking out of my mailbox, I internally sigh. Yes, even though the hard copies have yielded some good stuff that has made its way into our pages.

My experience editing Stoneboat has, in just over a year, made me revise my writer mindset. I am trying to cultivating a love for the ease of electronic submission. I remind myself that it’s both faster and cheaper to submit electronically. That sometimes the turn-around time is quicker. That I don’t have to stand in line at the post office. These are pluses. Big pluses. I have gotten to the point where, when I see the “electronic submission preferred” line, I comply without bemoaning the loss of my old tradition.

Whenever I come across a stubborn journal that requires paper submissions, though, I get excited. It’s a lot more satisfying to hold my manuscript and savor the crisp paper smell while I’m standing in line at the post office than it is to hit “send” on my email while I’m simultaneously checking Facebook and shuffling my way through an iTunes play list. There’s something to be said for doing it old school, no matter how many trees die in the process.

Originally posted on the Stoneboat blog.